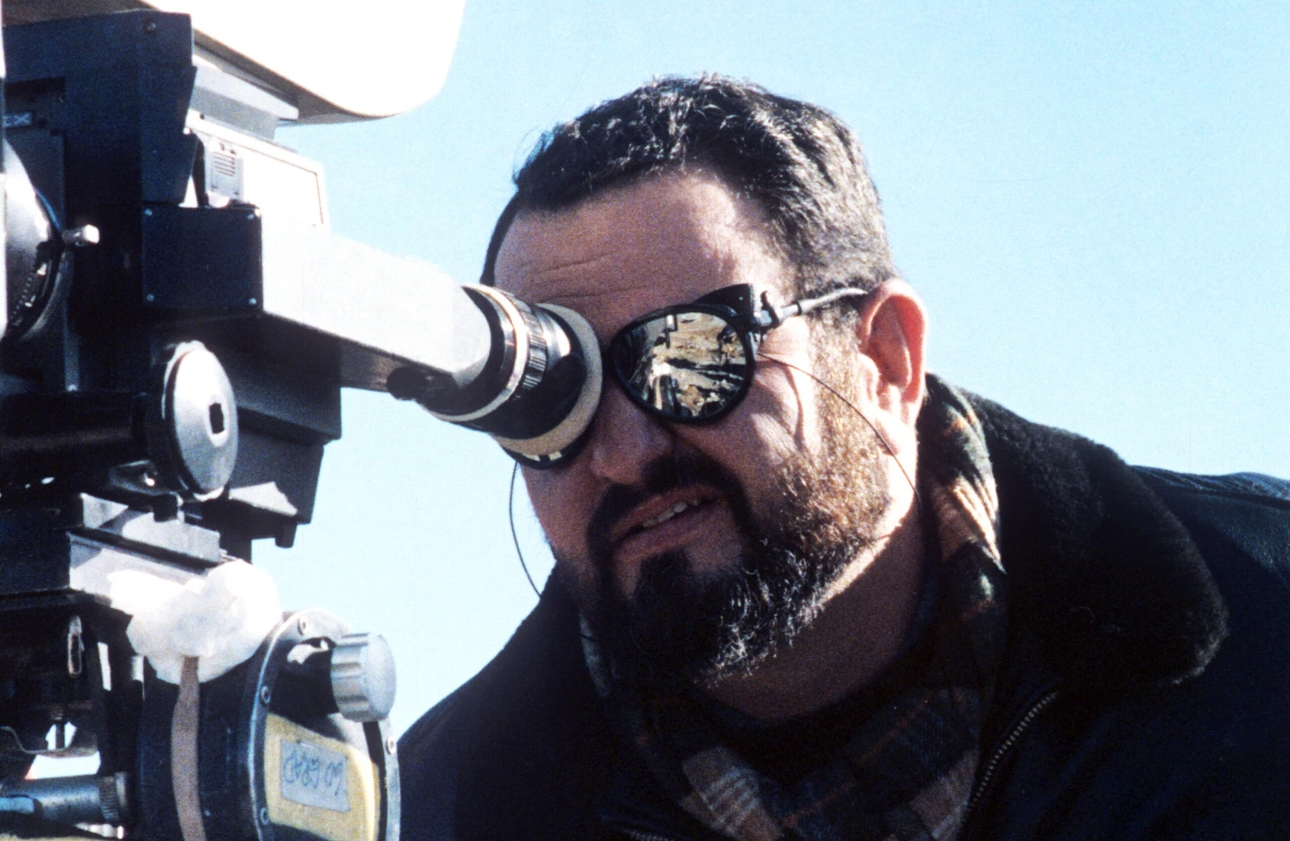

John Milius may be one of the most underestimated traditional storytellers of the last 50 years. Best known for his screenplay for Apocalypse Now, Milius was one of the best-known and best-paid screenwriters in 1970s Hollywood, particularly known for warrior tales featuring dramatic monologues and allusions to American heroes like Theodore Roosevelt.

The underestimation may be because, from his film school days onward, Milius became known for loving esprit de corps, American history, and the military. University of Southern California classmate George Lucas recalled Milius punching a professor who refused to show Lucas’ finished short film because it would make the other students feel bad. While contemporaries like Oliver Stone became known for stories about underdogs dismantling the conservative establishment, Milius wrote scripts about outsiders (maverick cops like Dirty Harry Callahan, self-appointed lawmen like Judge Roy Bean) who criticized the establishment as tepid and exhorted returning to the honorable warrior life. When Milius turned to directing (Dillinger, Conan the Barbarian, Big Wednesday, Red Dawn, The Rough Riders, Flight of the Intruder), his action-oriented stories were often criticized as movie-length comic books, but have become more influential than expected. From Ukrainian soldiers painting Red Dawn slogans on Russian tanks to ongoing debates about how Conan the Barbarian prefigured the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Milius has been disreputable but never quite forgotten.

Calling Milius a traditional storyteller captures how he escapes usual rightwing/leftwing labels. He is often dismissed as an extreme rightwing director, in part for public statements extolling his love of guns and of generals ranging from Roosevelt to Genghis Khan. Pauline Kael dubbed him a fascist filmmaker in the 1970s. Yet one of Kael’s proteges, Paul Schrader, dubbed Milius the “master of the flash” because Milius’s behavior was clearly exaggerated for a public persona. Even as Milius cultivated a brand as “the only conservative in Hollywood,” he befriended and collaborated with prominent liberal storytellers like Stone (who wrote the original draft of Conan the Barbarian) and Steven Spielberg (who paid Milius to write the USS Indianapolis speech in Jaws). Milius has said he prefers to be seen as the opposite of fascism: a “Zen anarchist” who lives by the samurai’s bushido honor code while advocating for limited government regulation. As a person and a storyteller, Milius defies easy categorization.

If Milius can’t be reduced to rightwing/leftwing, liberal/conservative dichotomies, it is clear that he can be called a traditionalist storyteller. Inspired by filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa and John Ford, most of Milius’ stories follow warriors seeking a path to justice or enlightenment. Usually, their search clashes with how modern civilization expects them to behave. Unable to get help from the modern world, they look to some past figure to inspire their search for honor: Conan recalls his father’s instructions about “the riddle of the steel,” while recruits in The Rough Riders recall their fathers fighting in the Civil War. They crave honor in inhospitable times and refuse to give up on the search.

Milius’ traditional vision may be especially clear in an area where it does not seem obvious: how he explores the complexity of war. Interviewed by the Chicago Tribune in 1997 while preparing The Rough Riders, Milius talked about war as a paradox. “Men go off to war because they really want to, not knowing what it’s going to be. They think it’s an adventure, a romantic fantasy. And, of course, it never is. People are brought together and forced to do something that is truly unnatural to man—kill each other. But in doing this sort of extraordinary self-destruction, man seems to bring all of his virtues to bear.”

That quandary, how violence can bring forth carnage or virtue, is key to Milius’ work. While he is famous for writing lines like the “Do you feel lucky, punk?” speech in Dirty Harry and directing scenes like high schoolers exploding tanks in Red Dawn, Milius’ vision of violence is rarely as one-sided as it appears. Particularly compared to later action directors like Zack Snyder, Milius is notable for how much nuance he offers.

On the one hand, Milius unquestionably craved the warrior’s life. Like his idol Ford, Milius sought military service but a medical disqualification (Ford’s vision problems, Milius’ asthma) kept him out of active military service. In the documentary Milius, his son Ethan argues that a sense of loss about never going to Vietnam is fundamental to his father’s stories. Reading and writing stories about death and glory enabled Milius to experience the warrior’s life he never experienced himself.

Yet for all the exciting action scenes, Milius makes his heroes more complicated than they may appear. Several movies (Dillinger, The Wind and the Lion) feature protagonists who realize their worldviews are not too different from their perceived enemies, raising questions for the audience about whether violence is getting the expected results or whether honor may be something more than being a good fighter.

Other Milius movies follow a lone protagonist who finds that living with honor as a warrior is harder than it looks. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, Red Dawn spends its first half making guerilla warfare seem fun, and the second half showing how war is making the heroes traumatized and feral. The speech that Milius wrote for Jaws, Quint describing what is like to be on the U.S.S. Indianapolis when it sank, rides the tension of how horrifying and exciting it sounds to survive a shark attack. Apocalypse Now makes war look simultaneously attractive and grueling. The first Dirty Harry movie depicts Harry as taking harsh measures to get justice but also aware he is an exception (his department tolerates him because they can give him “every dirty job”) and that few others can follow his standards.

Even Conan the Barbarian, a movie about a hero who seeks vengeance, ends (at least in the director’s cut) with Conan pondering how much his ended quest defined his life and then declining to emulate his enemy when the villain’s followers try to worship him.

None of these stories explicitly resolve the tension between violence’s cost and glory. In part, this could be because Milius has always been more poet than scholar. He has spoken about learning storytelling from California Beatniks as much as from books and boasted about never bothering to learn the three-act screenplay structure. He enjoys seeing how far he can take this vivid, paradoxical vision about war without necessarily offering a clear answer to the tension.

While this tension may be confusing at first, it has traditional sources. Milius’ refusal to give an easy answer to violence is precisely what makes him a direct filmmaking descendant of Ford and Kurosawa. Ford famously made John Wayne into a movie star with his westerns, but the best Ford westerns (The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance) made Wayne into an ambiguous figure who had to reform himself as much as he reformed “the things gone wrong in this here town.” Kurusawa’s iconic seven samurai, not to mention his ronin warriors in Yojimbo and Sanjurō, never looked cool while fighting and were always aware of the lonely path that came from their chosen vocation. All three filmmakers understand the tension between seeking the old ways, but never giving into the idea that living an honorable warrior life is simply about being tough.

Given Milius’ traditional bent, it is interesting that even though his friends and colleagues regularly cite Ford and Kurosawa as influences, they rarely portray violence with the same ambiguity. The Empire Strikes Back might be read as showing the costs of the violence in A New Hope, but war looks fun throughout Lucas’s original Star Wars trilogy. Terrence Malick’s movies about war depict fighting as messy while nature looks peaceful, spiritual. Spielberg’s adventure and war films tend to focus on how fallible warriors are (God saving the day in Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ryan wondering if he did well with the life others died for in Saving Private Ryan). Schrader’s movies about warriors (veterans like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, reformed outlaws like Norville Roth in Master Gardener) are fascinating but clinical explorations of neurotic men using violence wrongly.

Martin Scorsese’s gangster movies might get the closest to the tension that Milius explores. His stories about urban war can feel flippant when Scorsese pairs Mafia killings with jaunty rock music, but the killings are rarely fun to watch. The protagonists have fun doing violence, but pay the cost of living without honor. The difference between Scorsese and Milius is primarily that Scorsese rarely offers a hero seeking to genuinely live out honor, certainly not successfully. It is interesting that Scorsese is also Milius’ contemporary who has come closest to the Christian tradition (returning to Catholicism by the 2010s after years of being a lapsed Catholic). The Euro-American tradition of faith has seen many people misuse just war theory for terrible purposes but offers a framework to understand where things went wrong.

Much has been said (and needs to be said) about what honor looks like and what happens when violence is used for the wrong reasons. Especially when one side of the conversation treats warrior honor as a fiction while the other side equates honor with toughness, it is important to look to traditional storytellers like Milius who refuse to give easy answers. Whatever warzone his heroes find themselves in, they find the warrior’s life is complicated. The best of them lean into that tension rather than escape it. Honor proves worth pursuing, no matter the cost.