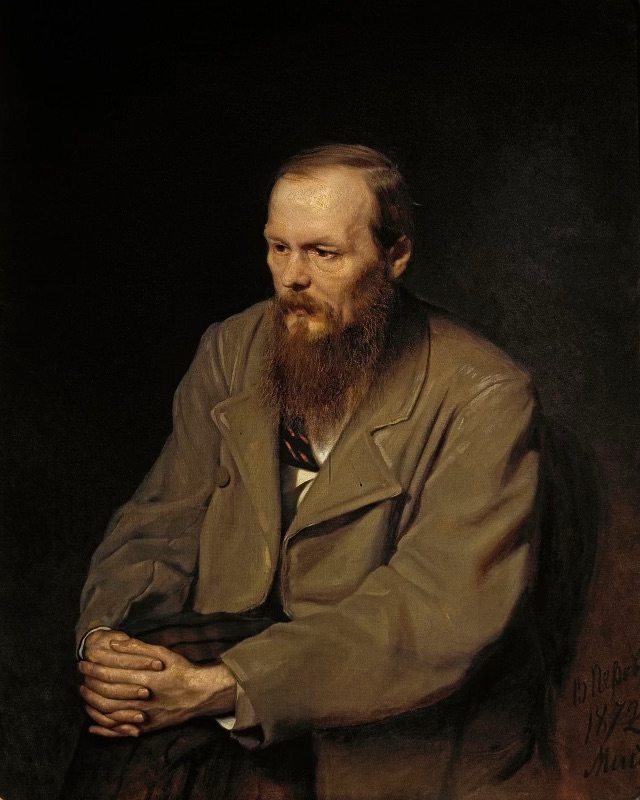

In his monumental work The Gulag Archipelago, the anti-communist activist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn famously wrote that “Thanks to ideology, the twentieth century was fated to experience evildoing on a scale calculated in the millions” (Solzhenitsyn 174). Nevertheless a century before Solzhenitsyn survived to tell the tale of Soviet tyranny, another Russian writer, Fyodor Dostoevsky, ominously warned the world that the social and political “ideologies” which were destined to produce the totalitarian regimes of the past century were alive and well in the university yards and campus alehouses of mid 19th century Russia. Of all the texts in Dostoevsky’s great literary corpus perhaps none are as prophetic in this regard as Crime and Punishment. The novel’s protagonist, Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov (Rodya) commits murder for the sake of testing an intellectual hypothesis. This essay argues that although the concept of Utilitarianism serves as philosophical justification for Rodya’s crime, the primary, and even more sinister cause is an adaptation of the “Great man theory.” Rodya’s fixation with these two beliefs not only inflamed his pride and egotism, but also led him down the path of internal ruin.

The novel begins with Rodya, a 23 year old former university student in the throes of intense agitation. For a month he has been obsessively ruminating over a deleterious scheme; to murder Alyona Ivanovna (his neighborhood pawnbroker), and plunder her copious stores of money. Yet, the Imago Dei in Rodya (ie. his soul) constantly reminds him of how evil this conspiracy really is, he ponders, “Oh God! How repulsive this all is! Can I really, really… no its rubbish, absurdity” (Dostoevsky 7)! Rodya’s anguish is further intensified when he receives a letter from his mother, Pulcheria, stating that his beloved sister, Dunya, has been wrongly accused of adultery and has agreed to marry a selfish and domineering man named Luzhin simply out of financial desperation. More to it, Pulcheria has been borrowing money to send to Rodya in hopes of him returning to law school.

Eventually Rodya finds himself in a tavern wherein he has the opportunity to eavesdrop on a conversation between a university student and a young officer. During their discussion, the student rationalizes Rodya’s interior urge to murder Alyona via an argument based on Utilitarianism. Formalized by the British philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, the ethical theory of Utilitarianism posits that the morality of an action is grounded solely in whether it satisfies the desires of the majority of people. You see, Alyona is a first-rate wretch. She is very affluent and yet a renowned cheapskate. She extracts exorbitant amounts of interest on her customers and she treats her half-sister, Lizaveta, like a slave, even going so far as to physically abusing her. Alyona spitefully reigns with lucre while multitudes of people with untapped potential struggle in poverty. Thus, the student concludes, “A hundred, even a thousand good deeds and undertakings could be planned and performed with the old woman’s money…One death and a hundred lives in exchange—it’s a matter of arithmetic” (Dostoevsky 47)! Moreover, Alyona’s wealth could serve as a means of freeing Dunya from an unhappy marriage to Luzhin, securing Pulcheria’s financial freedom and getting Rodya reenrolled in university.

Considering this encounter between the student and the officer to be a prophetic affirmation of his own inner thought processes, Rodya commits to killing Alyona and her sister Lizaveta, albeit the latter merely out of panic since she caught him in the act. As the novel progresses, Rodya’s psychological state deteriorates as he grapples with his guilt-ridden heart. From this point on the primary motivation behind Rodya’s committing murder becomes manifest. At the heart of his sinister plot is a version of the Great man theory. A hermeneutic of history first popularized by the Scottish scholar Thomas Carlyle, the Great man theory proposes that history is fundamentally a chronicle of assertive men of action establishing by virtue of their innate superiority the course of civilization. An articulation of Rodya’s own vile adaptation of this ideology is manifested during his conversations with Porfiry Petrovich and Sonya.

Following the event of the murders, Rodya and his loyal friend Razumkhin make their way to the police station in hopes of retrieving the two items he had previously pawned to Alyona. Upon arrival the two friends begin a discussion with Porfiry Petrovich, the police officer in charge of investigating the crime. As they dialogue, Porfiry discloses that he had read Rodya’s article on the nature of crime. Rodya explains that in the article he divides mankind into two groups: the “extraordinary men”, whom he describes as “lawgivers and trailblazers of humanity” (Dostoevsky 181) and “ordinary men”, who are naturally well-mannered and born to serve the status quo. In order to inaugurate a new modus vivendi, he insists that extraordinary men must transgress the established rules of society. Rodya even goes so far as to claim that extraordinary men are within their rights to kill, if it allows them to achieve their destiny. Rodya states that “even if it’s necessary to step over a corpse, to wade through blood in order to attain his goal, then in my opinion he may, according to his conscience, give himself permission to wade through blood” (ibid). Porfiry found Rodya’s thesis to be suspicious and asks if he considers himself to be such an extraordinary man. This question proved to haunt Rodya throughout the novel.

After weeks of inner turmoil, Rodya finally met with Sonya and confessed to killing Alyona and Lizaveta. In the course of their conversation, he continues to demonstrate his internal division. He tells Sonya that he came to see her in order to relieve his suffering and out of shame he accuses himself of having a “wicked heart” (Dostoevsky 287). Moments later, however, he relapses into an eerie disposition of self-aggrandizement. He admits to Sonya that his crime was a test to determine if he was valiant enough to be an extraordinary man. Neither economic need nor a Utilitarian desire to benefit society were the core causes behind the murders. Rather, Rodya’s crime stems primarily from his obsession with power and self-importance. He makes this clear when he declares to Sonya, in true machiavellian fashion, “I wanted to become Napoleon, that’s why I killed….Power is given only to the one who dares to bend down and pick it up. There is only one thing that matters, only one: to be able to dare” (Dostoevsky 288, 290). Sonya, though a prostitute, nonetheless exudes Christ-like compassion and can only respond by saying “what have you done to yourself?” She urges Rodya to repent to Christ, turn himself in— resolving to stand by him through it all.

In the final analysis, while both ethical Utilitarianism and the Great man theory influenced Rodya’s crime, it is clear that the latter of the two theories held primacy over his mind and heart. When Rodya’s intellectual plot crumbled before his face, he nonetheless continued to defend his articulation of the Great man theory, telling Dunya that “this idea was not at all as stupid as it seems now, given my failure” (Dostoevsky 359). Rodya’s comment to his sister demonstrates why surrendering these intellectual aspirations proved so difficult for him; they facilitated a deep sense of pride and self-importance. These two theories were like twin demons pulling Rodya down into a hellish existence. While the Great man theory served to feed Rodya’s ego, Utilitarianism granted him a useful philosophical paradigm to justify his nefarious actions. To surrender these ideas and admit himself to be a failure was an affront to his ego—one he concluded was too difficult to bear. The painful reality for Rodya was that his guilty conscience continuously waged war against his soul and so proved himself to be a fraud; he was not the extraordinary man he thought he was.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Michael R. Katz. Crime and Punishment: A Norton Critical Edition (Norton Critical Editions). W. W. Norton & Company; First Edition (December 1, 2018)

Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn. The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary

Investigation (Volume One), Basic Books; Vol. 1 edition (January 30, 1997)

Debunking the Great Man Theory of History.” Andrew Bernstein

andrewbernstein.net/2020/01/the-great-man-theory-of-history/. Accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

Driver, Julia. “The History of Utilitarianism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University,

University, 22 Sept. 2014, plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history/.