One of my favorite illustrations by Charles Addams (1912–1988) is a gleaming picture of an underground car tunnel. The proportions of the cars, the bright lights, and the curve of the tunnel walls all have a precise quality. Then I see the policeman in the right-hand corner of the illustration, sticking his finger into a hole in the tunnel wall. Water drips from his hand.

The illustration captures an aspect that made Addams’ work so memorable: the drawing is funny not just for the reference (a man putting his finger in a wall like the proverb about a Dutch boy saving a town by putting his finger in a leaking dike). More than anything else, the drawing is funny because everything else looks so right.

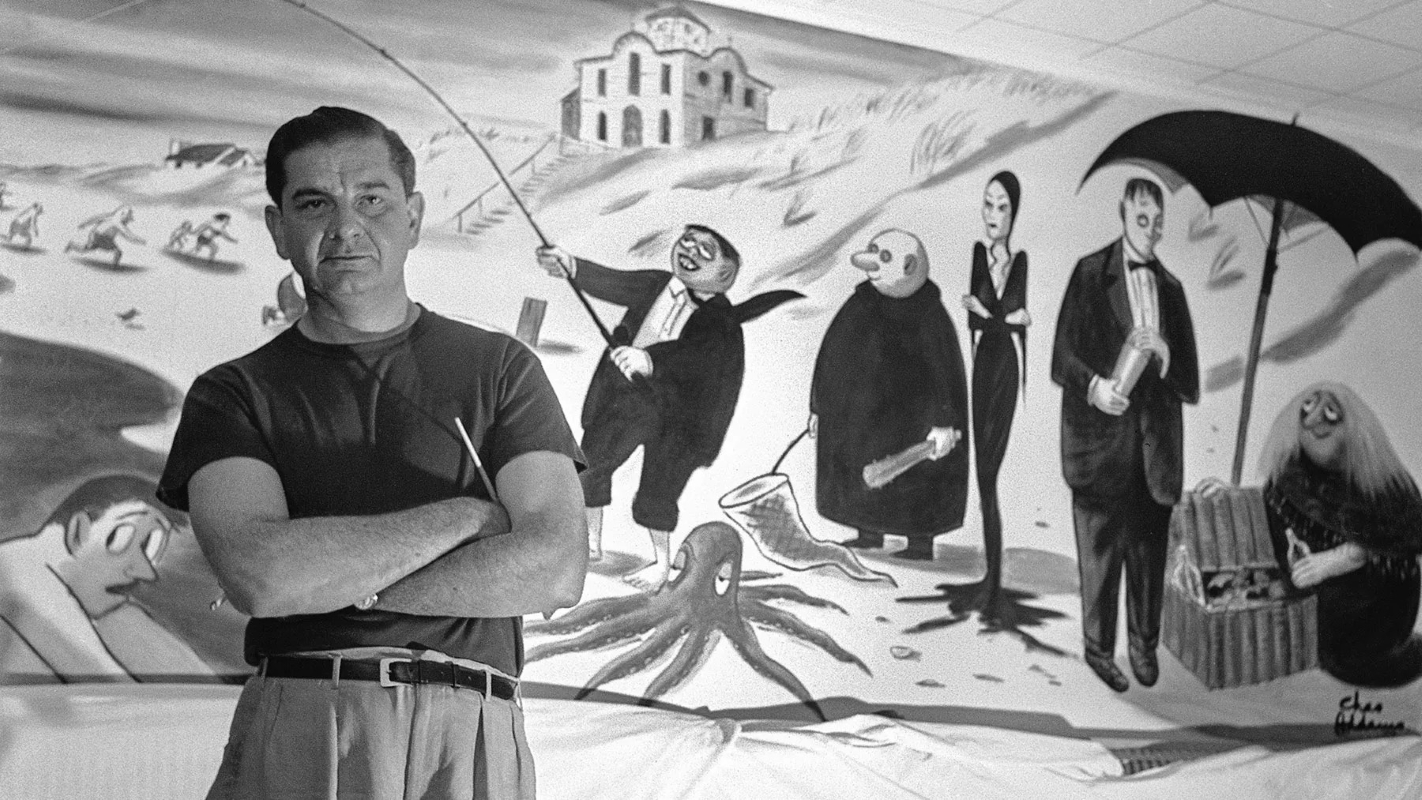

During his lifetime, Addams was one of the most memorable New Yorker cartoonists, particularly known for recurring illustrations about an eccentric family in a haunted house. Those illustrations inspired the 1960s TV show The Addams Family and all its spinoffs (currently, the Netflix show Wednesday produced by Tim Burton, but more iterations will likely come in the future). If you like the ghostly and ghoulish, you can thank Addams for helping make it mainstream in America.

It may not be correct to say that Addams’ work was tongue-in-cheek, which suggests camp (everything being playfully excessive). He did combine darkness with humor in a way that contemporaries like Vincent Price or Robert Bloch also embraced, an attitude that fell out of fashion after the 1960s. Gore (particularly via true crime stories, especially ones featuring serial killers) replaced humor to the point that “horror entertainment” too often means never-ending violence today. As violence for violence’s sake has lost its novelty, many critics have wondered whether the gothic has become too predominant in America. Have we become too obsessed with creepiness?

A strong case could be made that part of the problem is that American culture has forgotten what the gothic is for. We find darkness fascinating, but have lost our reverence for the supernatural. The more horror becomes about human depravity without any discussion about the hereafter (what eternal values shape our sense of what is horrific? What comes after death?), the easier it is for horror stories to offer shocks without asking questions about what makes something shocking.

Another part of the problem may be that Americans have become too serious about horror. Re-reading From the Dust Returned, Ray Bradbury’s collection of short stories about the paranormal Elliot family that Addams illustrated, I was struck by how much Bradbury offers a Midwestern sense of history and pathos in his ghost stories. Some gothic storytellers today get close to Bradbury’s rich poetic sensibility. I have written about Russell Kirk elsewhere, a Michigan native whose short stories often explored the rich gothic atmosphere of his home state. I also appreciate how filmmaker Scott Derrickson takes time to make his characters’ journeys feel grounded even as fantastic things occur around them. But unless one makes a point to seek out niche genres like literary horror (literary fiction that edges into horror), it can be hard to find stories about murder and mayhem which are also funny and intelligent. The poetry so present in Bradbury’s work, or the comedy so present in Addams’ artwork, does not appear in mainstream culture as much as it did in the days when anyone could find it in the New Yorker.

More than that, American entertainment in general has missed something so central to Addams’ work: only once we know what is beautiful can we know what is horrible.

As Wilfrid Sheed notes in his introduction to The World of Charles Addams, Addams began his career hoping to draw knights and castles, taking inspiration from Arthur Conan Doyle’s historical adventure novel The White Company. It was only after discovering his dark sense of humor sold better that Addams became famous. Sheed notes how important that background is to understanding the appeal: no one made a modern New York building look better than when Addams drew it. “He was in love with the sheer thingness of things.” Other artists like Saul Steinberg praised Addams as the first artist to offer cartoons in which “modern architecture was drawn seriously and intelligently.”

As time went on, Addams cultivated his dark sense of humor and, to some extent, a public persona to match (most famously, his third and final marriage occurred in a pet cemetery). But as Sheed observes, any interview with Addams “founders about halfway on the rock of Charlie’s manifest sanity and profound good nature.” It turned out that one didn’t need to be Uncle Fester to produce gothic stories. If anything, one needed to be Norman Rockwell. A clear idea of the tasteful and the beautiful had to be present at the start to capture weirdness so well.

This sanity and good nature recur throughout Addams’ art, becoming more obvious with subsequent viewings. From a well-kept cemetery with a do-it-yourself grave engravers’ kit to Gomez Addams instructing Wednesday and Pugsley to give “a nice big sneer now” for the family photo, Addams’ artwork abounds with shocking things, but always framed in an aesthetically (and by association, morally) clear universe.

As I prepare to enjoy the next season of the current Addams Family adaptation (and ponder what iteration will come in a few years), I keep hoping more people will appreciate how this sense of beauty is key to the best gothic entertainment. Only when we understand what is beautiful can we tell intelligent stories about the grotesque.